We are a group of creative people who help organizations make their ideas beautiful.

The Rich Interior Life of Jazzy Danziger

I thought I’d introduce you to Jazzy Danziger by giving you a little house tour.

Boy, was that stupid.

We were talking about a recurring dream she has where her childhood home becomes something surreal and alien, morphing into different shapes. “I've had this dream for 25 years, since we moved out. The house is in a different form every time. Sometimes it's like a big fishbowl; in one dream, it’s shrunk to half its size and someone’s built a mall around it.”

The house-as-metaphor thing is a current creative preoccupation for her; she’s working on a novel about a photographer who becomes entangled in a family’s history while photographing the estate sales they manage.

“I’m trying to talk about how our identities are shaped by the houses we grow up in. The way we can be haunted by houses,” she told me.

Once after writing a short nonfiction piece on a bar napkin, Jazzy won a trip to Louisville, a tour of the Four Roses Distillery and several bottles of whiskey.

House as metaphor? I can get behind that. Jazzy—a fierce multi-hyphenate badass who dreams of working on Mattel—is just the kind of artful study in contradictions who can appreciate the subversion of so-called “domestic” topics. So, okay, I thought, maybe Jazzy is a house.

And a house fits, right? Because a Paradowski bio is supposed to reveal something to you, to grasp at the cobwebs at the corners of your personhood and pluck out something more elusive, illustrative. It’s meant to give you a tour of a place you think you know quite well, only to introduce you to a spare door you’ve never noticed before. And inside it—a hidden staircase, a forgotten west wing, one that’s always been there but somehow escaped your notice, like in that fever dream you had when you were eight. Here it all is, and it’s been here the entire time. But now it’s different.

But this kind of literary party trick is hard to pull off when it comes to Jazzy. Because anything that could be said about Jazzy has already been said—by fawning poetry critics, sure. But, more to the point, by Jazzy herself. In a defter, more eloquent, infinitely more compelling way than I might say it. And, more often than not, in sharp little metered couplets.

Let me explain. My failing metaphors aside, Jazzy is not a house. Jazzy is a poet.¹ (An accomplished one.) But more importantly, Jazzy is someone who believes in transparency. And it shows.

__________

¹ Also, a creative director, which has less overlap in the Venn Diagram than you might expect.

Cracking the spine of her book (University of Wisconsin Press, copyright 2012, Brittingham Prize in Poetry), I see she’s mined and manipulated and finely milled her personal history far better than any dusty bio ever could. In it—perhaps paradoxically, for a book entitled Darkroom—everything is rendered in clear white light. The true emotional wrenching isn’t in the monster lurking around in the shadows. It’s in the sterile normalcy of cold linoleum or the sharp, clean brightness of a plastic banquette seat. Lit with an overhead fluorescent, there’s nowhere to hide. Every detail is stark and chosen with specificity. Jazzy’s poems are places that are meticulously decorated², for maximum devastation.

__________

² Virginia Woolf, perhaps apocryphally, was called the Interior Decorator of Literature by a snide Bloomsbury contemporary. I’m sure Jazzy would have a few choice words about the gendering of that descriptor, but let’s pretend for a moment that it was an honorific instead of a diss. That’s how I would’ve meant it, anyhow.

If you know her, this comes as no surprise.

Visiting Yayoi Kusama's "Let's Survive Forever" at WNDR Museum Chicago.

Her unflinching impulse to turn a spotlight on even her squishiest insides isn’t for the faint of heart. But it’s also not out of character. That’s because, in the workplace and out, Jazzy champions the kind of radical honesty that, in others, would seem inauthentic at best—and, at worst, like a lethal liability for an office environment. (Wasn’t it the scorpion who cried “radical honesty!” as he plunged a stinger into his frog friend, sending them both to the bottom of the river?)

Jazzy, though, spends every workday proving that radical honesty isn’t a trap, nor a quaint cliché embroidered on a throw pillow. She sets out radical honesty on conference room tables like a tray of canapés. She makes it the prerequisite for any discussion, big or small. And, perhaps most bravely of all, she models it again and again so that even those of us who are slightly more distrustful of confessionals (read: all of us) can gain our sea-legs.

It seems terrifying (especially for someone who self-identifies as having “terrible imposter syndrome,” as Jazzy does). But that’s also what makes it a noble pursuit. Equal parts idealistic and idiosyncratic, of a stripe that only a poet could bring to the advertising world. And it pays off. With this, she furnishes a space where Creatives can become something even more rare and daring: humans. (And as it turns out, humans can do some great work. Sometimes even better than Creatives.)

How does a person come to be like this?

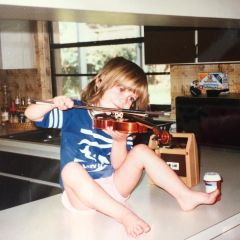

Growing up in Florida in the '90s meant four things: The Orlando Magic, theme parks, devastating hurricanes that would kick off a lifelong obsession with natural disasters, and frequent Space Shuttle launches (and sonic booms).

Maybe it starts with the name. (I know you’ve been wondering.) When the first thing people want is for you to defend why you call yourself what you call yourself, it stands to reason that you’d get good at starting every relationship on the side of transparency. If Jazzy is at all weary of explaining the origin of her name, she doesn’t let it grate on her. (Long story short: too many Jessicas; someone had to find a way to tell them apart.)

But even a rock-solid ethos of transparency can’t keep a person from underselling themselves sometimes. And as such, the common explanation for how Jazzy became Jazzy is a bit of an under-sell.

Because, while perhaps anybody can be a Jessica, not just anybody can be a Jazzy.

If you put "formal attire requested" on the invite, Jazzy will be there. With bells on.

To illustrate: One day, I walk into a team happy hour to join a reservation under her name. The hostess and bartender exchange a look. “Are you Jazzy?” I shake my head. “Is she here yet?” It’s clear that they want to know what someone called Jazzy might look like.³ “She actually couldn’t make it,” I tell them. The disappointment is palpable, sinks to the bottom of the room like an un-muddled sugar cube. Some people grow into their names, or try year after year to scrunch themselves into them like an ill-fitting ring, turning a little green at the edges. But I have a hunch that Jazzy was always going to be Jazzy, even as she tells me that it’s her “life’s mission” to discover who she is.

But the lesson is learned: If you make a reservation under the name Jazzy, when you show up, you’d better be Jazzy. Jazzy—it goes without saying—is.

__________

³ Here’s what she does look like: Jazzy’s hair is always on just the right side of fantastical; right now she’s crowned in an icy hue that’s somewhere between Blondie’s Debbie Harry and Candyland’s Queen Frostine. Her brows are, as the kids are absolutely no longer saying, “on fleek.” She can achieve a smokey eye that inspires fear and respect. She has a makeup TikTok. It’s very good.

Her name is on the door, so that’s what you get. (There’s that transparency thing again.) And as forced as it might be, there’s a reason I keep circling this dumb house metaphor when it comes to Jazzy. It’s because of a phrase I couldn’t get out of my head after we talked. A phrase that people in writers’ circles tend to toss around. Folks say, “she’s got a book in her.” (Often—unsurprisingly, considering the spiteful and mercurial nature of writers—it’s used as a put-down: “She’s only got one book in her.”)

Jazzy is incapable of feeling despair while immersed in a body of water. It's the Florida in her.

But here’s the thing. Like that childhood fever dream, or that phonebook-sized tome you had to read in college, the interior is bigger than the laws of physics should allow. Jazzy doesn’t have just one book in her. She has the fucking Library of Alexandria. And yeah, a darkroom. And maybe a pottery studio? Or a recording studio. A Cher Horowitz closet. A woodshop. An aquarium. And, yes, that one door that just appeared out of nowhere—why have you never noticed it before? One that leads to...winding stairs? A stalagmite-draped cavern somewhere below the basement? A whole other house, the photo-negative of the first? Can you see it, in the dark? Wait, here we go. Look. Here’s the switch.