We are a group of creative people who help organizations make their ideas beautiful.

The New Science (and Art?) of Image Making

MidJourney, DALL•E, and Beyond

There were two things at the front of my high school debate classroom. The first was a standard-issue desk — a hulking, mysterious fusion of dense iron and warm oak veneer — whose sole purpose seemed to be propping up the feet of my teacher, Mr. Les Kuhns.

Mr. Kuhns was harsh and honest and familiar. Most of the kids in his class quickly learned to drop the “Mr.” and just bark out “Kuhns!” When he wasn’t chewing on a cigar, or flying his two-seat plane out of the Midwest, you could find Kuhns wedged recumbently between a rolling chair and his desk, searching the ceiling through thick spectacles while his floppy lips pontificated under two tight cantilevered curls of a waxed mustache that framed his flaring nose. Imagine William Howard Taft as an angry catfish. That was Kuhns. He was a gregarious grump with a booming Kansas accent that rattled the windows —and his pupils. For a 14-year-old emerging from the hormonal fog and academic desert of middle school, Kuhns and his classroom were a creative and intellectual oasis.

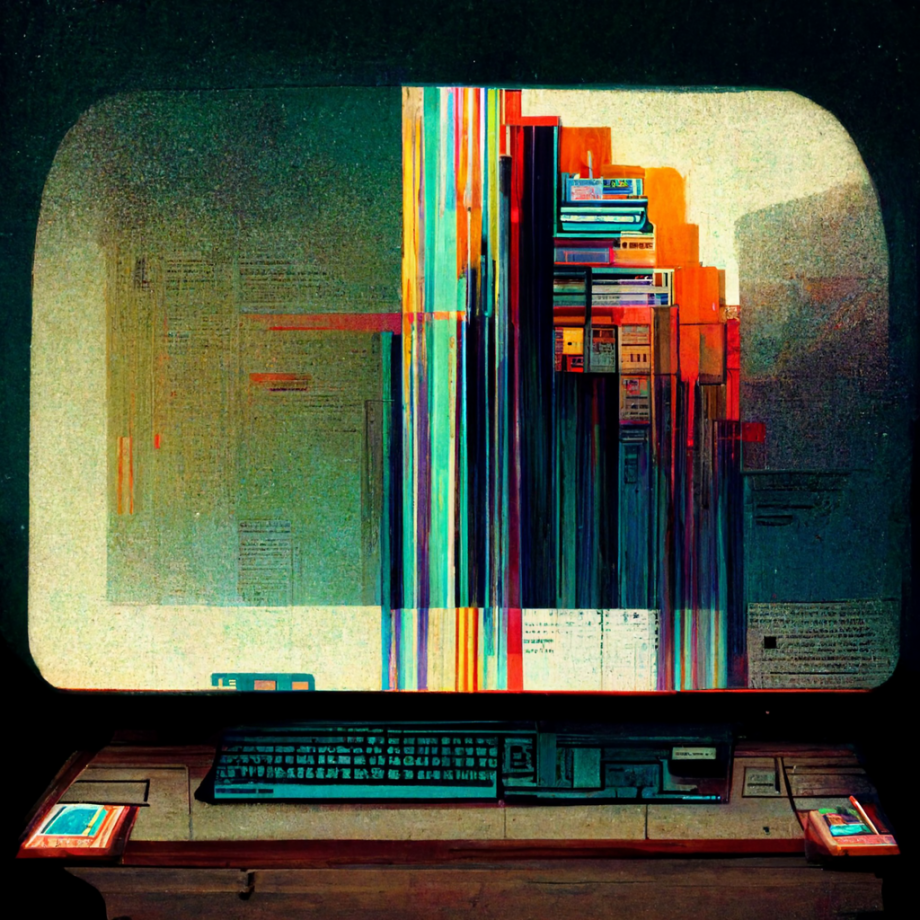

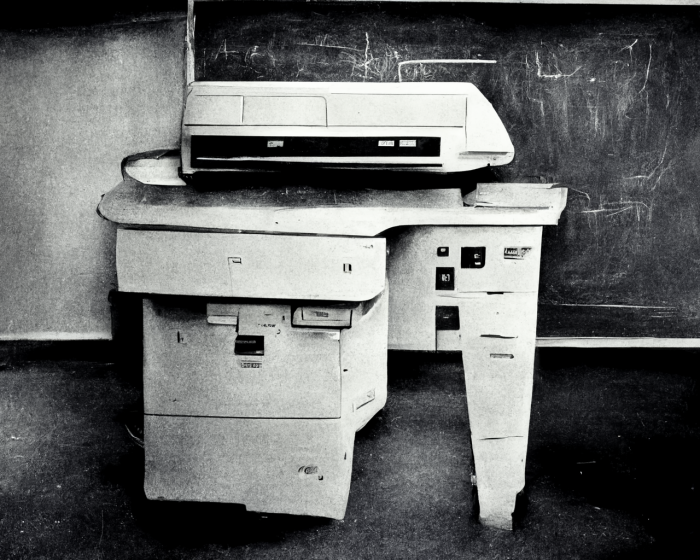

The second fixture earning its spot at the front of Kuhns’ classroom was just as massive. It was a special piece of imaging technology: a late 1980s-era Xerox photocopier, or “copy machine,” as we lovingly called it. There was another one down the hall outfitted with one of those coin slots, but this one was free. I could smell the hot toner halfway down the hall on my way to class each morning, and the hum of lasers and rollers and plastic parts grinding away greeted me as I unloaded my backpack and got to work. That thing was always running. It had to be if we wanted to win.

“photocopy of a photo of a 1980s-era Xerox photocopier in an empty classroom,” created with MidJourney

Debate class was half lecture, half information harvest. Every year, Kuhns bought these massive books full of “evidence,” which were really just article snippets sourced by a bunch of Ivy League researchers and sold to twerps like us. This was the raw material for substantiating our claims against the competition. It was essential. And the copy machine was the beating heart of our evidence distribution system. Sure, it was slow. And loud. And perpetually paper-jammed. And yes, some degree of quality was sacrificed in the images it created. But for a gang of gangly freshmen that desperately needed to slop together cases and muddle through countless rounds of policy debate, that Xerox machine represented the best technology had to offer. It was a beautiful, glowing knowledge factory, and I loved it.

“It’s hard to describe, but there have been a few moments in my life when time freezes and a portal to the future is suddenly plunked down in front of me.”

But one morning as I approached Kuhns’ classroom, it was especially quiet. The hum was gone. No clacking plastic parts. No grinding lasers. I figured we were probably out of toner or something. When I opened the door, no one was using the copy machine. We had plenty of toner, but the operation was at a standstill. And there was a new piece of furniture. Bolted to a rickety, wheeled cart was a shimmering computer that captivated my huddled friends. One of them waved me over, “hey Andy, check this out!”

“group of gangly students huddled around a computer,” created with MidJourney

It’s hard to describe, but there have been a few moments in my life when time freezes and a portal to the future is suddenly plunked down in front of me. You know those stories about how a person’s life quickly rewinds and flashes before their eyes when they’re about to die? It’s kind of like that, only in these instances, I see all of our lives fast-forwarding. I watch the inevitability unfold as a piece of technology rips a hole in the status quo. Woah, this thing is going to… change things. Surely we’ve all felt this at some point. If not right away, maybe when it’s too late.

This was one of those moments.

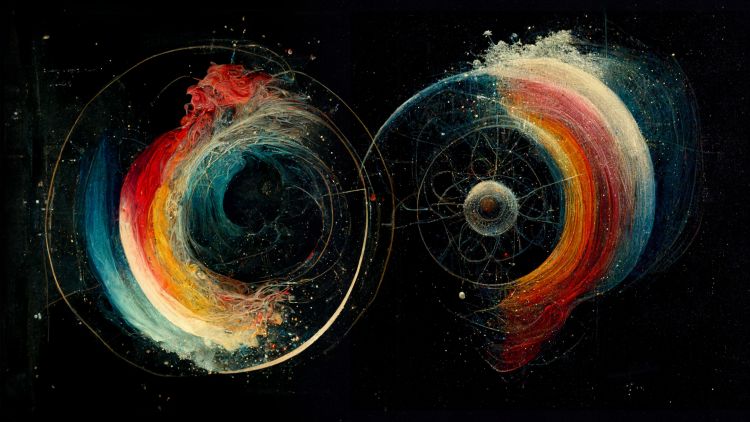

“A hole ripped in the status quo,” created with MidJourney

My friend explained that there was this new thing in beta called “Google!” (yes, with an exclamation point), and it let you find anything on the internet just by typing in a few words on a webpage. It was nuts. It was magic. And I knew immediately that my relationship with the copy machine was pretty much over.

This is how Google[!] looked when we first met. (Source: Wayback Machine)

It happened again a couple years later when I bought my first digital camera, and pitched my darkroom supplies.

And again, about a decade later, when I was staring at the blue dot on my iPhone that followed my progress on a map as I drove home from work. (The Rand McNally Road Atlas my parents insisted I keep in my car came out only once more to go directly into the recycling bin.)

And again when I went to our public library and tried a 3D printer for the first time, which catalyzed a whole mini-renaissance complete with: optical illusion vases that looked like my kids, the creation of a wall-mounted drawing robot, application of Google’s “Quick, Draw!” data set, training a neural network on the entire Google Fonts library, and…well, things got a little out of hand.

And then, at the end of last year, it happened again.

A couple years ago, I trained a neural network on 69,300 lowercase character shapes from the Google Fonts library. This is a tiny sample of the nearly infinite characters lurking it the resulting model’s latent space.

By Christmastime of 2021, AI-powered generative art tools were becoming more numerous by the day. I tried several: pixray, pytti, disco diffusion—plus countless derivative notebooks spawned from the brainwork of Ryan Murdoch and Katherine Crowson. Images of things that didn’t actually exist were commonplace, but now those images were becoming easier to generate — with just words. And thanks to the combination of VQGAN and CLIP technologies surpassing their one-trick-pony GANcestors, the generated images were beginning to take on new, infinitely-variable forms.

I cranked out some holiday-themed images (among a dizzying array of other things) as my own proofs-of-concept, and I was impressed. But the results were consistently dystopian and impressionistic at best. There were hints of potential, and it was all pretty cool, but it still wasn’t quite there. Yet.

A little later I bumped into MidJourney (thanks for the invite, Matt). And then OpenAI’s DALL•E. (Nvidia Research has an elaborate tool called Gaugan 2 that comes with a publicly playable demo. Google has two projects going: one called Imagen, and another called Parti. Oh, and now Meta’s got one called Make-A-Scene. Apple’s doing their own thing they call Gaudi, which has something to do with hallways. And as I write this, Stable Diffusion was announced by Stability AI, whose lead generative AI developer is the aforementioned Katherine Crowson, the one who set this whole craze in motion in the first place.)

“What does this kind of synthetic creation mean for creators? For Art? Does it mean my relationship with image creation is over?”

Most of these new tools work in roughly the same way: 1.) type a string of words or phrases into a text field, 2.) push a button, 3.) collect yourself and process the emotional impact of seeing your imagination instantly and effortlessly materialize on screen. The tech is maturing nicely. And quickly. It’s like doing a search on Google Images (or a stock image site), only this time the images are created—not sourced—according to your exact specifications, in real-time.

The Xerox machine has stopped humming. The portal is opening again (and so is Pandora’s box). This time, the future that’s fast-forwarding in front of me is almost in perfect focus: any person can conjure any image they like in any style with any composition—instantly—simply by describing it. It’s nuts. It’s magic. But there’s another part of this future I can’t squint my way to understanding. What does this kind of synthetic creation mean for creators? For Art? Does it mean my relationship with image creation is over?

“silhouette of a person standing in front of a portal to the future,” created with MidJourney

I wasn’t working as a librarian when I found Google. And I didn’t have any shares of Kodak stock when I plugged in my first digital camera. And I wasn’t working at Rand McNally when I used GPS on my first iPhone. But, I am a creative professional today. I can suddenly empathize with the animator at Disney who watched Toy Story for the first time. And the calligrapher reading a newspaper. And the candlemaker screwing in an incandescent bulb. Did MidJourney just /imagine me into a blacksmith?

Even as a self-proclaimed futurist, this feels… different.

“a hulking mysterious fusion of dense iron and warm oak veneer” created with MidJourney

MidJourney

Existential dread aside, I’ve found working with MidJourney and DALL•E to be an absolute joy. So much so that I find myself using one or both of them daily. The first of these tools I had the opportunity to play with was MidJourney, and one of my first prompts seemed apropos: “infinite possibilities.”

“infinite possibilities” created with MidJourney

After each prompt, users are presented with a grid of four different low-resolution results that can either be “upscaled” into higher resolution outputs, or used as the basis for another set of four “variations” on an individual output. The process has built-in addictive mechanics that generate anticipation as each iteration gradually materializes, and variations are refined. The whole thing is mesmerizing and intoxicating.

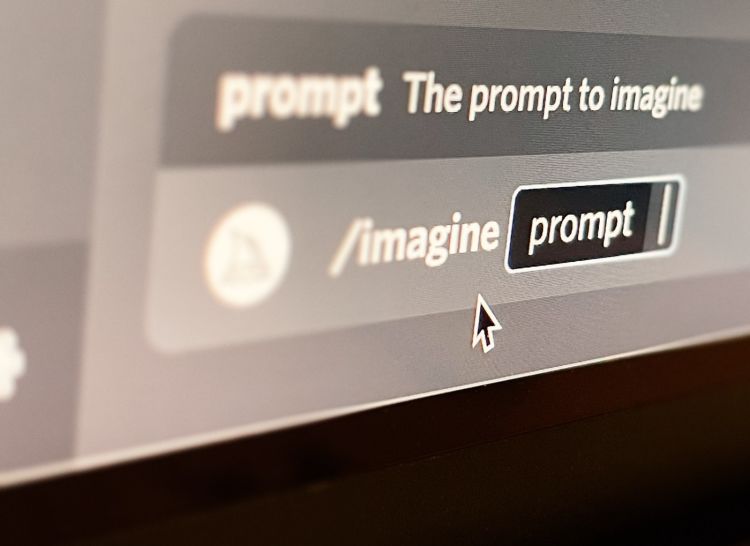

To start creating, users just log into Discord, open the MidJourney Bot channel, and type “/imagine prompt:” in the chat field, followed by a description of the desired output.

Once I got over the initial holy-woah-what shock, I started probing the tool for its strengths. MidJourney seems to delight in fielding abstract concepts. Prompts like “as above, so below” (R.I.P. Lodge 49) reveal otherworldly, but legit, standalone artwork. Likewise for phrases along the lines of “everything everywhere all at once.”

“as above, so below” created with MidJourney

“everything everywhere all at once” created with MidJourney

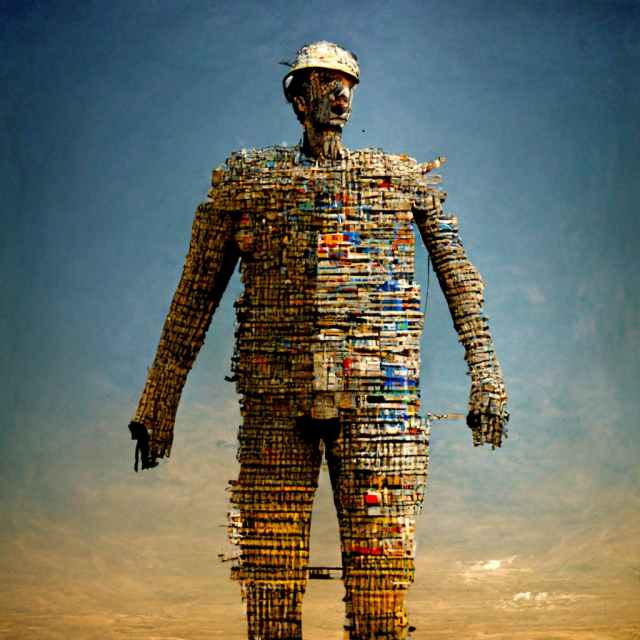

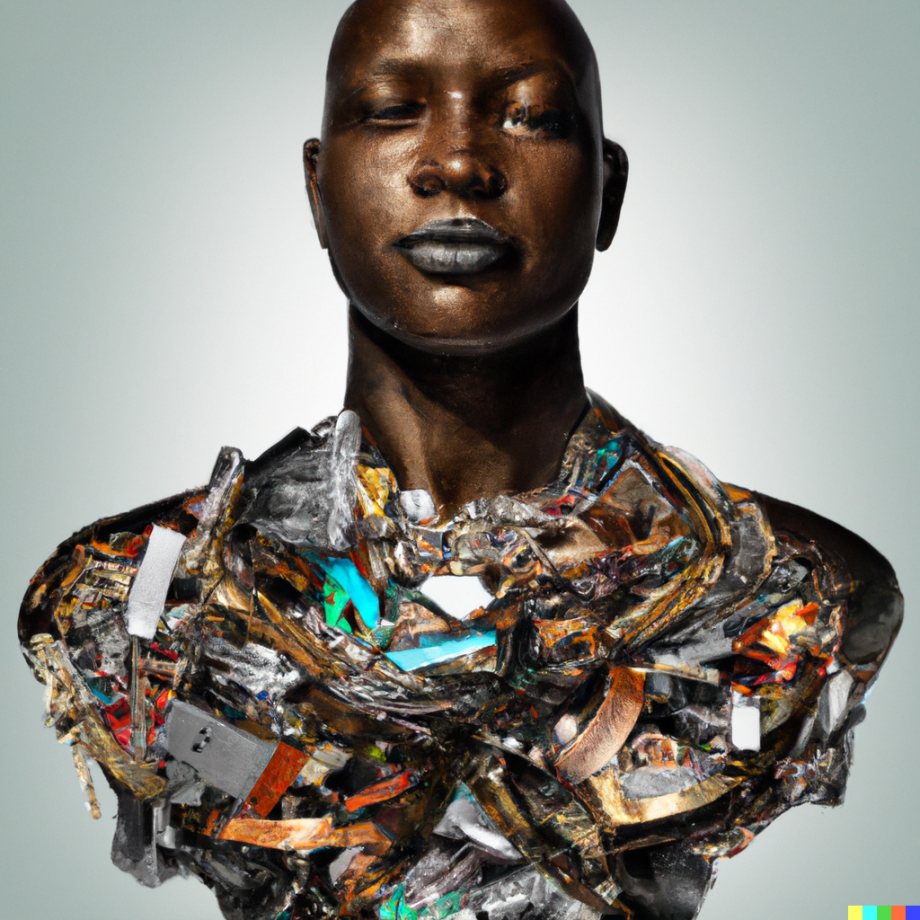

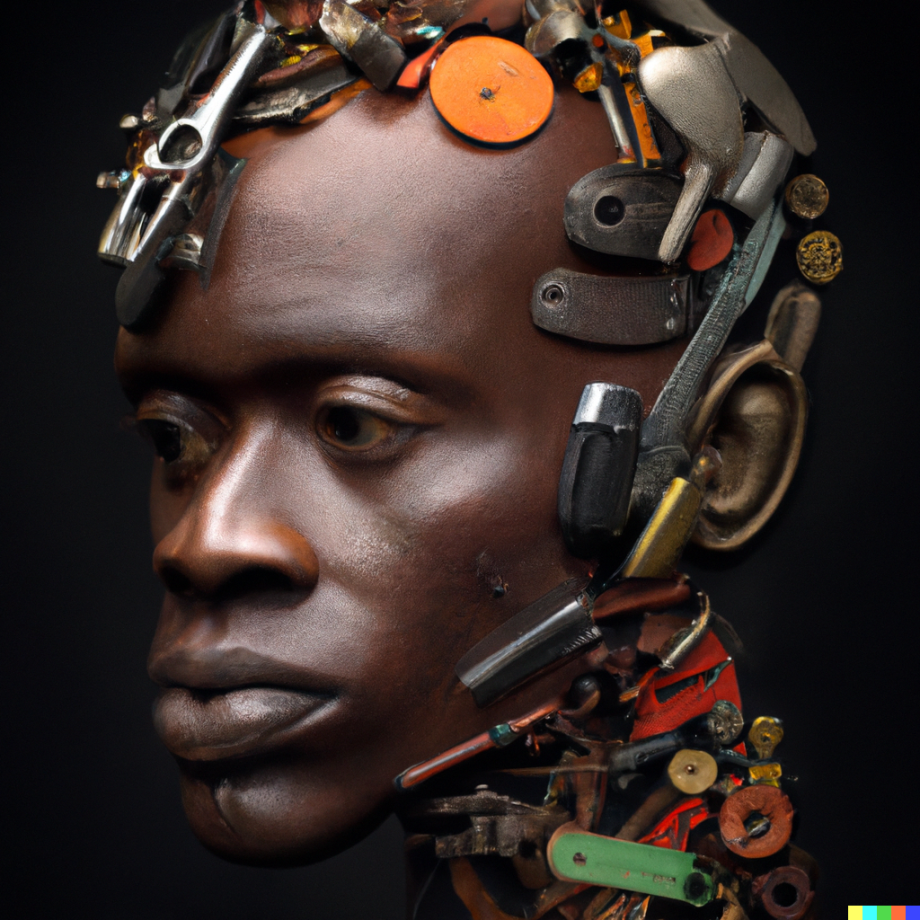

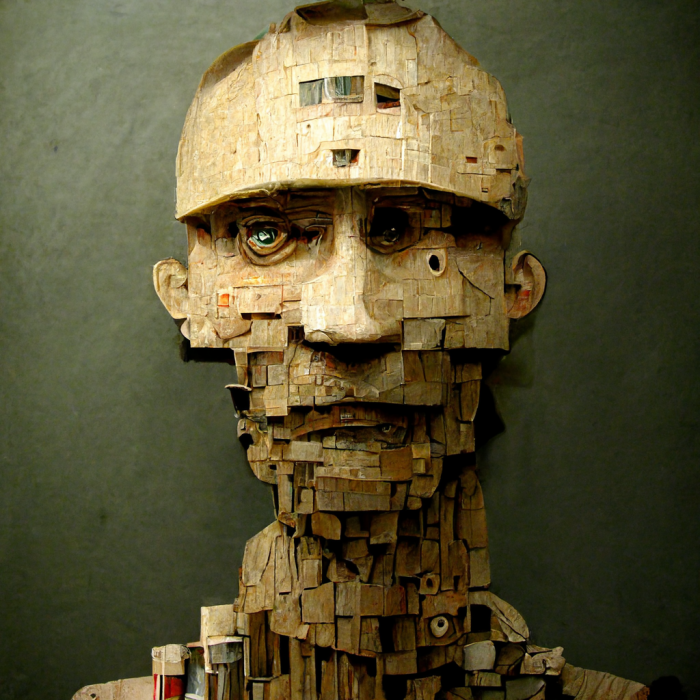

MidJourney seems equally comfortable in the tangible space. I tossed it “man made of man-made materials,” and got more stunning, instantaneous results. Variations on a single output looked less like minor computer-generated tweaks and more like an artist’s careful iterations as they study a particular subject matter. Each generation is a window into the tool’s underpinnings which feel more soulful than they ought to. One can’t help but ascribe meaning to the visions MidJourney returns, or at least scan them for clues about how we got here.

“man made of man-made materials” created with MidJourney

Iterations and variations of “man made of man-made materials” created with MidJourney

A funny thing happened when I shared the “man made of man-made materials” outputs on our company Slack channel. Matt, our Business Operations Coordinator for Technology at Paradowski, read my prompt as “man made of marmalade,” which seemed like a great phrase to forward to MidJourney. So I did.

“man made of marmalade” created with MidJourney

Then I had this silly idea for a new company that sold Manmade Marmalade™. If they needed marketing and communications work, could MidJourney help our agency help them? The answer was a resounding yes.

So far, so good on Manmade Marmalade™ #midjourney logo options. But why stop there? pic.twitter.com/DX0wyyM9qb

— Andy Wise (@andywiseguy) August 11, 2022

In the hands of anyone with an idea and the words to describe it, this kind of tool becomes a shortcut to shared understanding. And in the hands of a capable creative team, this generative art direction could shortcut weeks of concept development. Instant iteration used to be an oxymoron, but not anymore. In a matter of minutes, this imaginary condiment brand was already taking shape, and so was a whole new way of creating.

Nine variations of “art, science,” created with MidJourney

Beyond simple prompt regurgitation, MidJourney’s neural network has also managed to model a BFA-grade capacity for the elements and principles of design. It has grokked the ingredients for aesthetically pleasing composition, rhythm, balance, and texture. The evidence of artistic intuition is at once alarming and humbling. But it’s not perfect. There’s an apparent bias toward things like illustration and primary color schemes (and a spooky recurrence of silhouetted figures draped in cloaks), but really only when left to its own devices. After all, we humans still create the prompts. For now. At least mostly.

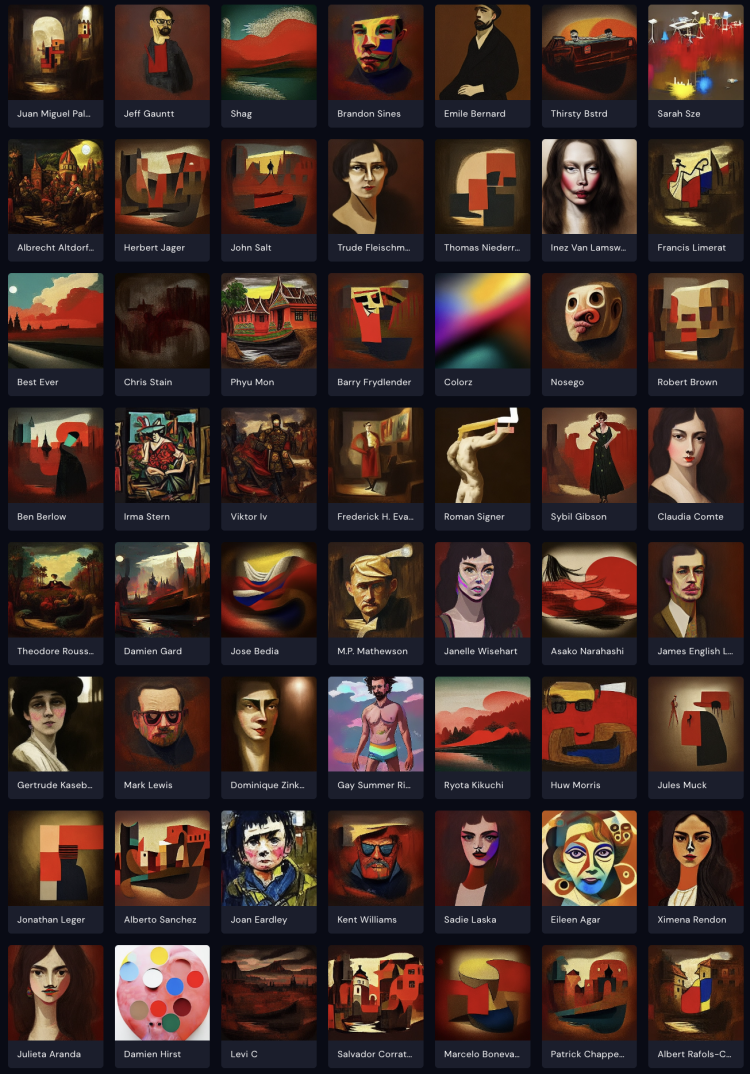

Things get more interesting with the inclusion of style descriptors. Prompts that include phrases like “crayon drawing,” or “Octane render, 8K,” or “in the style of Jean-Michel Basquiat” generate corresponding results. This approach was well-documented in the early days of VQGAN + CLIP image generation (and, again, by “early days” we’re talking, oh, a year ago) and has become an accepted and expected use for synthetic image generation. MidJourney even has its own visual dictionary for the impact certain stylistic cues might produce.

I wasn’t just an avid copier as a kid, I was also a reader. At least as long as the books were written by Roald Dahl. I’m not sure I would have read anything at all until Mrs. Johnson introduced my first grade class to James and the Giant Peach. An orphan escapes his wicked aunts by flying an oversized piece of fruit over the Atlantic Ocean with the help of some seagulls and a bunch of bugs, ultimately skewering his vessel over Midtown Manhattan through the spire of the Empire State Building. Now here was a story. I loved the words Roald Dahl used to describe things, and the images they inspired in Nancy Ekholm Burkert.

“tiny boy silhouetted against a giant peach,” created with MidJourney

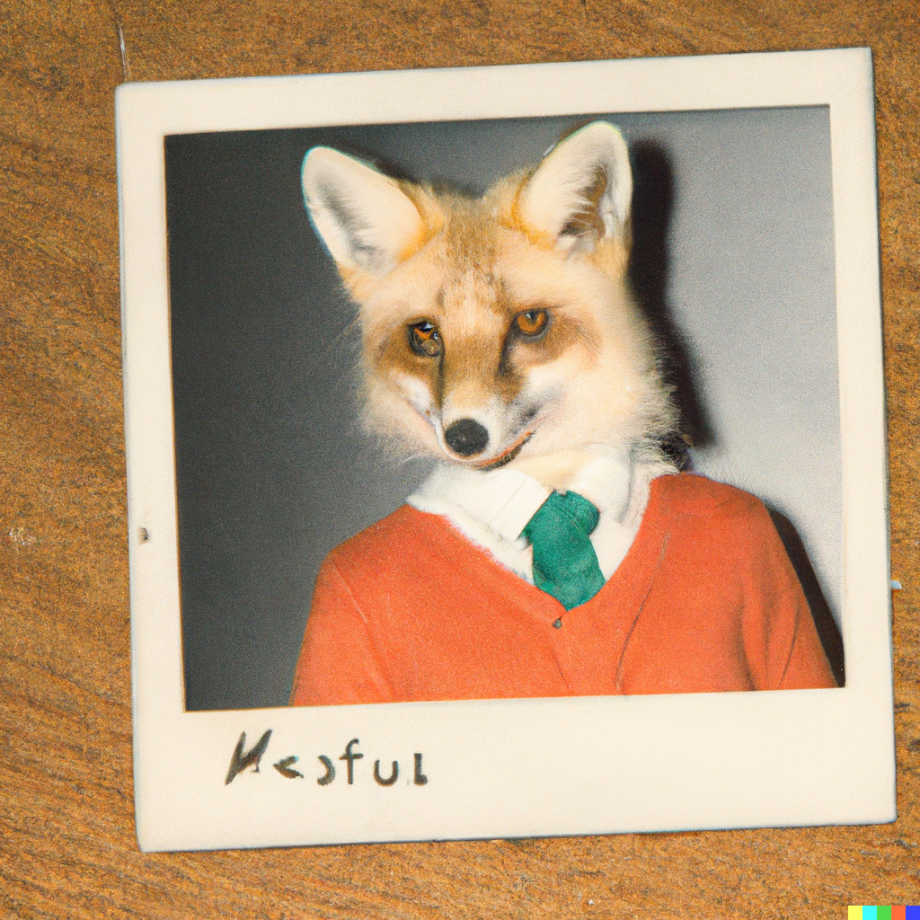

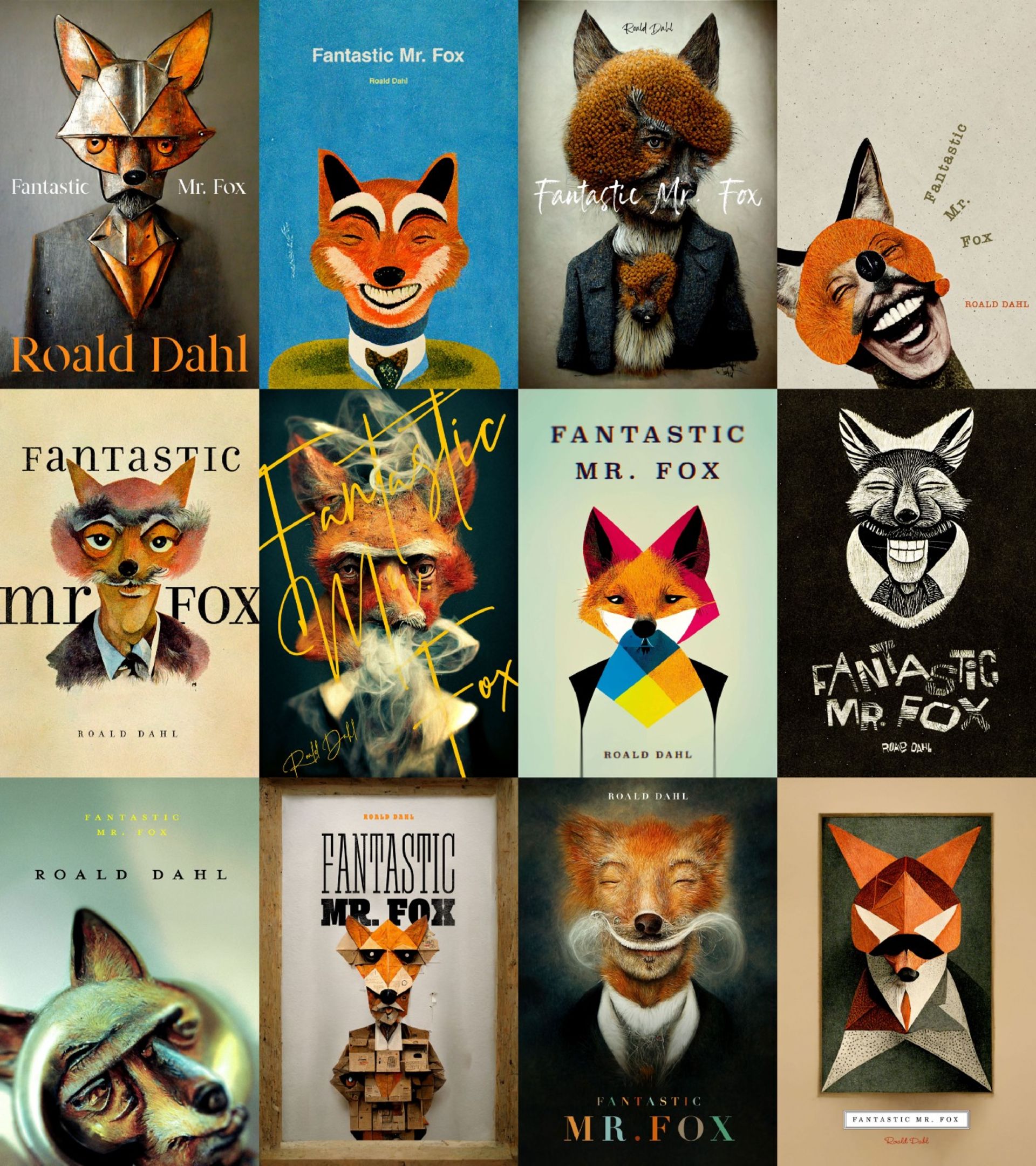

Now I enjoy reading Dahl’s work with my kids, and recently they were quite taken by his Fantastic Mr. Fox. After putting the boys to bed one night, I wondered how text-to-image tech might assist with an assignment from Puffin Books. Could it help me design a new book cover for this old classic?

With MidJourney humming along, in no time at all, I had the equivalent of weeks (or months) worth of illustration concepts. My direction was quick and simple, and the output was a variety of styles that would be either financially irresponsible to even consider, or flat out impossible to produce in a pre-MidJourney world. I added some basic typography (for the moment, MidJourney is awful at that sort of thing, thank goodness), and with little effort I was staring at a tidy set of options fit for a pitch to Puffin.

A sample of 12 Fantastic Mr. Fox book cover designs I created with the help of MidJourney.

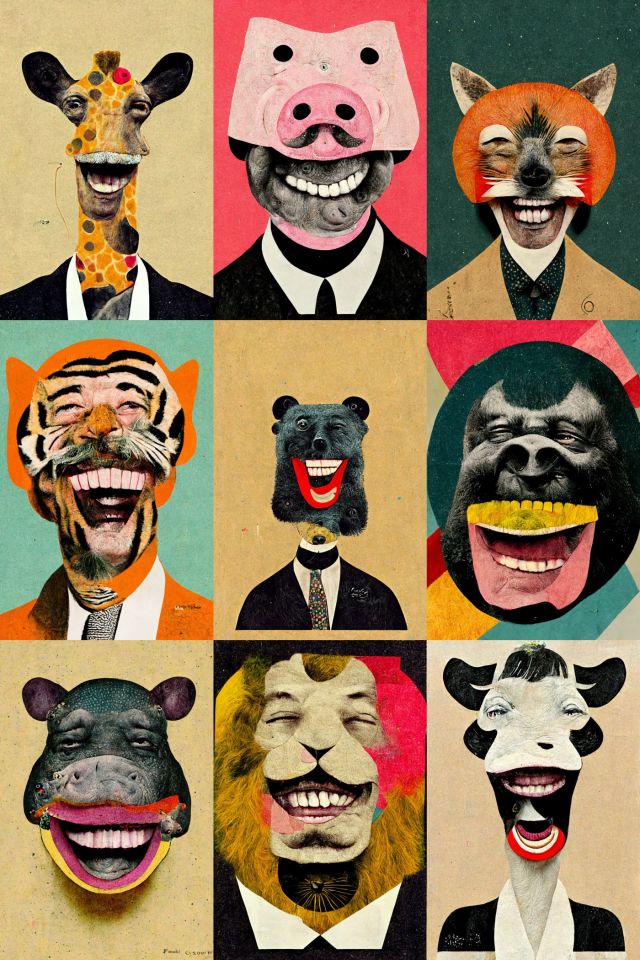

As is the case nearly every time I interact with MidJourney, my work spawned another tangent I couldn’t help but explore. A particular style caught my eye and inspired me to create a MidJourney menagerie of multiple animals. I found my brainwaves surrendering to a new frequency MidJourney was broadcasting.

The more I let go, the more exciting things became. Sure, I had my own ideas, but it started to feel like even those weren’t always originating from my brain. There was this emerging inspiration flywheel unlike anything I’d ever experienced as a creator. The faster it spun, the faster it spun.

“Flow” is one of those things that’s hard to describe, but universally sought after in the creative field. One of the many brilliant aspects of MidJourney is its ability to align with and facilitate that special cognitive state.

“Creative flow shares the feature of coming to mind rather than found through effort, and may be surprising, but rather than a single idea which solves or restructures a prior problem, flow unfolds over time. The ease of processing is part of the emerging creation, not a process subsequent to it.”

— Charlotte L. Doyle, Creative Flow as a Unique Cognitive Process

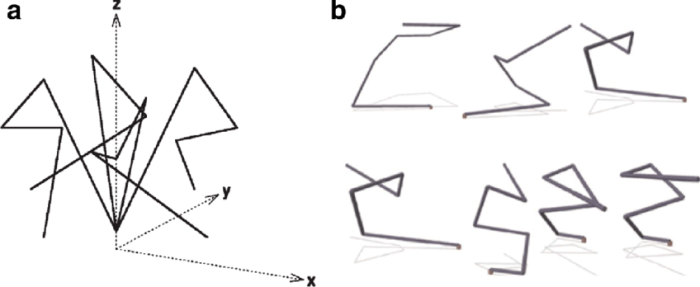

Its near-immediate feedback grabs the creator by the hand and says, “come on, let’s go slowpoke!” Next thing you know, you’re off and running down unexpected and beautiful paths that were never on your map. But how could they be? Your map has two dimensions; MidJourney’s has hundreds. And it’s only one tool. There will be others. But for now, there’s at least one more to explore.

DALL•E

When OpenAI published the results of its first version of DALL•E at the beginning of 2021, anyone who was paying attention was floored and immediately disappointed there was no public beta. But we didn’t have to wait long until DALL•E 2 showed up. First it was a select few, and now anyone can sign up to be stupefied.

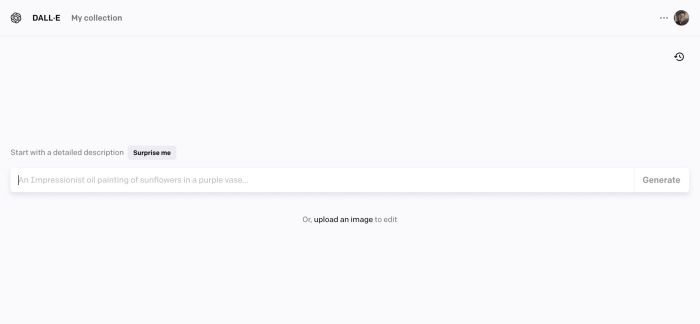

DALL•E’s interface is beautifully simple. It’s always the quiet ones.

DALL•E offers an unassuming web application interface whose simplicity beguiles its magic. The experience is familiar: users are given a basic text input field and a button that reads “Generate.” After a few seconds, several outputs appear. Presto. The quality of the images DALL•E generates is insane. Computers aren’t supposed to be able to do this.

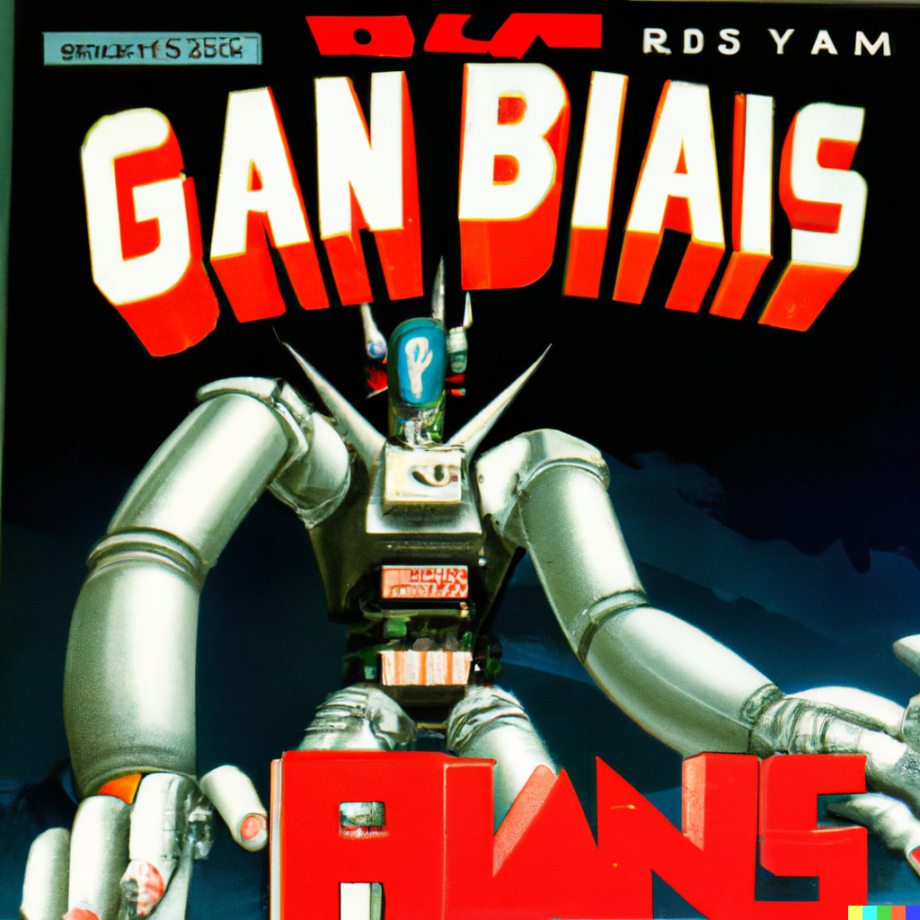

Naturally, I challenged DALL•E with the same things MidJourney had already tackled. Starting, of course, with more Fantastic Mr. Foxes, more men made of many man-made materials, and some retro video game box art concepts for good measure.

Is it just me, or is that second robot image headline trying to say “GAN BIAS?” Is the neural network trying to make contact?

While it can handle a range of styles, DALL•E’s true passion seems to lie with photography. The brooding whimsy of MidJourney’s more illustrative, fine art spirit is traded in DALL•E for something more literal—formal, even. Results seem to be biased toward realism. Abstract concepts often return what looks like ghostly stock photo results, rather than the painterly wisdom you’d expect from MidJourney.

“computers are not supposed to be able to do this” outputs from DALL•E and MidJourney

“brooding whimsy” outputs from DALL•E and MidJourney

“the future looks bright” outputs from DALL•E and MidJourney

In exchange for less creativity from the AI, users are allowed more creative agency within the experience. There’s an option to upload an image and request “variations.” Users can even erase portions of an image to be filled in by DALL•E, much like Photoshop’s “content-aware fill” operation. This becomes a nice utility when you’re in the heat of creative iteration, but also avails the tool for other exploits. Seamless panoramic images, or “infinite zoom” videos can be had if users are willing to play with DALL•E in just the right ways.

A continuous panorama combined from 11 outputs of the prompt “abandoned theme park” given to DALL•E. I modified each output by shifting the image horizontally until only a portion of it was still visible, then filled the remainder of the image with transparent pixels and re-uploaded it to DALL•E. Because of DALL•E’s diffusion-based technique, the resulting images blend seamlessly.

An “infinite zoom” created by compositing the outputs of 15 different prompts given to DALL•E. I modified each successive output by making it smaller with a border of transparent pixels, and then used that as the input for the next prompt. By repeating the process, and combining the results, this zoom effect could go on indefinitely.

OpenAI continues to iterate on the features available to its users in an effort to scale efficiently, and ethically. Even while writing this article, the images returned with each prompt were reduced from six to four. And other things I loved about earlier versions have since been cut to curb liabilities. For example, I can no longer upload images of real people—even myself. Which is a real shame, because I was looking forward to meeting more doppelgängers.

DALL•E’s variations on the original (top-left) me.

There are exhaustive resources comparing these tools, because, well, they’re the only public horses in this race right now. My assessment: they’re both formidable, and seem to be evolving into their respective illustrative and photographic niches. I’m looking forward to more players in the space, and I’m looking inward.

Another continuous panorama I combined from DALL•E’s outputs of the prompt “impossibly tall sandwich with lots of different ingredients.”

Everyone’s super, now.

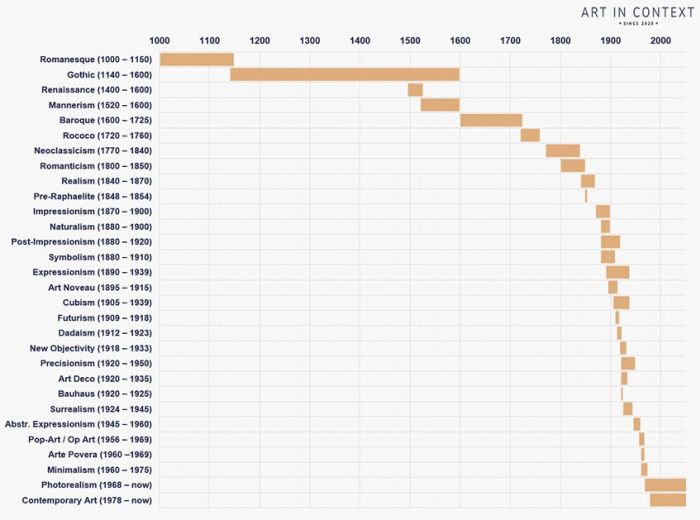

Historically, art has moved slowly. The Gothic period lasted for centuries. Futurism was a blip on the timeline of art history, and it lasted for years. What we call Contemporary Art has existed for decades, despite the modern advances in communication and distribution one might expect would hurry us along.

“A Brief Overview of the Art Periods Timeline” from Art in Context

But things are different now. Artistic influences can be mashed up in minutes. Complex abstract concepts can be brought to life visually at the speed of human thought. We can invoke a lifetime of creative style development with as few characters as it takes to type an artist’s last name. If the last couple of years have taught us anything, it’s that technology can accelerate change in any number of industries. Why should Art be exempt?

In Pixar’s The Incredibles there’s a villain called Syndrome. His master plan is to mass-produce superpowers, so anyone can become just as “super” as the real superheroes he resents.

At one point he declares, “…when everyone’s super… no one will be.” (Maniacal laughter ensues.) So what about image-generation superpowers? Is anyone super, now that everyone is?

I think so. Simply having access to tools capable of generating art doesn’t make us artists. And art won’t advance any faster because of MidJourney or DALL•E. The democratization of these artistic tools doesn’t guarantee a proportional increase in artistic output. Actually, the inverse is true.

“So what about image-generation superpowers? Is anyone super, now that everyone is?”

If you don’t believe me, think for a moment about how many people use cameras. Thanks to smartphones, that number is now 6.648 billion, or 83.72% of the world’s population. If you’re reading this, you are a photographer, like almost literally everyone.

Now, consider the work of Annie Leibovitz, whose artistic approach and vision endures despite smartphones, despite Photoshop, and despite any present or future version of DALL•E. You have a tool in your pocket capable of capturing a photograph, but you are no Annie Leibovitz. No offense. The tool does not an artist make. Or as Ansel Adams said, “you don’t take a photograph, you make it.” Paradoxically, as the image quality improves with each new version of MidJourney and DALL•E’s algorithms, and as technology’s reach grows, the opportunity to create something truly unique and artistic shrinks. It’s harder to stand out when we’re all wearing capes.

nice to know annie liebovitz da gawddes uses the same camera as me pic.twitter.com/IcpWUYcTFD

— James Ellis (@Mrelllis) April 27, 2014

MidJourney and DALL•E represent massive, seismic innovation, but Art doesn’t advance on behalf of technology, or based on how prolific we are. Art changes with the pace of human culture. It rewards original ideas. It’s dangerous to conflate the fidelity of synthetic images with the quality of human ideas. In this new world, the definition of “super” changes. And new powers are already beginning to reveal themselves.

“It’s dangerous to conflate the fidelity of synthetic images with the quality of human ideas.”

Artists are literally pushing the boundaries of what’s possible by hacking DALL•E’s inpainting for enormous outputs.

Inpainting with DALL·E 2 is super fun. With some ingenuity, you can create arbitrarily large artwork like the murals shown below – which I assume are the largest #dalle-produced images created so far. pic.twitter.com/DDQUMSmgYq

— David Schnurr (@_dschnurr) April 19, 2022

This was made using the DALLE-2 neural network to extend Michaelangelo's creation of Adam. pic.twitter.com/sIfTEjXgwO

— Far Left Kyle (@FLKDayton) July 2, 2022

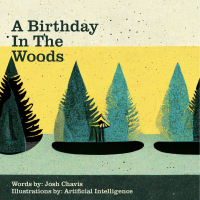

Brian Martinez published Lungflower, the first ever novel illustrated entirely by MidJourney outputs. My colleague, Josh Chavis partnered with MidJourney on a children’s book he was able to knock out in an evening.

Children’s book illustrated with MidJourney, written by Josh Chavis, Creative Director at Paradowski

2D designers have figured out new ways to create mockups.

Some mockups go further with these by trying to sell the posters as existing in a living breathing world, usually by having some people walk in front of them in long exposure. I didn't think DALLE-2 would be very good at this, but the results shocked me. pic.twitter.com/C6dclSrrYO

— Joseph Hillenbrand (@joeyeatsfridays) July 13, 2022

Nando Costa suggested brands might use this tech to create a custom logo for every customer.

Source: Nando Costa

Fashion design is ripe for text-to-image disruption.

Interactive designers are finding ways to jumpstart UI designs. Or even generate assets during production!

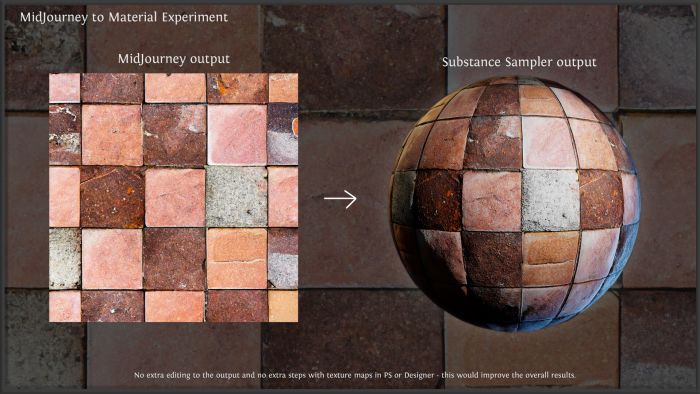

3D designers are loving MidJourney and DALL•E, for everything from concept art to texturing to generating entire game maps.

Created with MidJourney by Eric Bowman

Source: 80.lv

Tested using #dalle for texture fixing and texturing. It is going to save us so much time, if we streamline the workflow.#dalle2 pic.twitter.com/0WwljMHYNi

— Shahriar Shahrabi | شهریار شهرابی (@IRCSS) August 1, 2022

Motion designers and video artists are integrating this tech—and so are the tools they use.

Videos created with DALL•E by Paul Trillo

AI-loaded music videos keep popping up everyday.

And then there’s the Heinz commercial. Leave it to ketchup to be the first mover in AI-generated advertising. What a clever use of text-to-image tools as a cultural mirror.

Companies like Adobe have clearly seen the writing on the wall for a while now, and are investing aggressively to incorporate artificial intelligence into their creative tools. Tasks like skin smoothing and color correction that formerly required a skilled retouching specialist have been reduced to toggles and sliders in Photoshop. The inclusion of these so-called “neural filters” is evidence of the powerful influence AI can have on the processes (and careers) of image makers. The magic of DALL•E and MidJourney hasn’t made its way into Adobe’s creative suite of applications yet. But it’s coming. Again, not my prediction; it’s happening.

Adobe has already shortlisted “Portrait Generator” and “Latent Visions” as a future neural filters in Photoshop. The descriptions read, “generate unique photo realistic faces based on characteristics you specify,” and “generate abstract artistic concepts based on text strings.” What does it mean when AI-powered image generation becomes an industry-standard? What human limitations will text-to-image tools overcome, and what adaptations will they require of creators?

It’s official: the synthetic art movement is upon us. We’re all super now, whether we like it or not. For some creators, that brings anxiety and existential fear, but for a kid who dreamed of having a computer that could draw, there’s never been a more exciting time to be an image maker.

AI & The Creative Process

My youngest son is three years old, and recently discovered the concept of infinity, which revealed itself one evening through the calculator app on his iPad. First, he punched in as many nines as he could. Then, after mashing the multiplication sign awhile, the app capitulated on its skeuomorphic liquid crystal display, “INF.” He was delighted. “I made infinity!”

That’s sort of how I would describe the kind of synthetic creation you get with MidJourney or DALL•E. It is delightful. The possibilities are infinite. It feels like you’ve made something. But have you? Well, no, you haven’t really made anything—not if the thing you thought you made actually came from a computer. At least that’s what the U.S. Copyright Office’s Copyright Compendium said. But that doesn’t mean AI doesn’t have a role in the creative process. While the ends generated by AI tools alone are interesting, the creative means they enable are even more compelling.

Great artists steal.

When I was in college, there was no shortage of technological accoutrements. The internet was fast, and computers were everywhere. But there was one glaring anachronism. My frail art history teacher could be found before each class heaving a dusty carousel-style slide projector out of her trunk. It was a real time machine. For most of my classmates, our professor’s ASMR voice and her classroom’s dim lighting represented an invitation to sleep off a hangover, but I was wide awake. She clicked us from the Lascaux cave paintings to the Early Renaissance, through the Bauhaus and Dada, all the way to Kandinsky and Keith Haring and Banksy and beyond. I felt like an infant discovering the voices of its parents as the projector burned wonderful new themes into my brain. She was decoding Art’s DNA slide by slide, and I was spellbound.

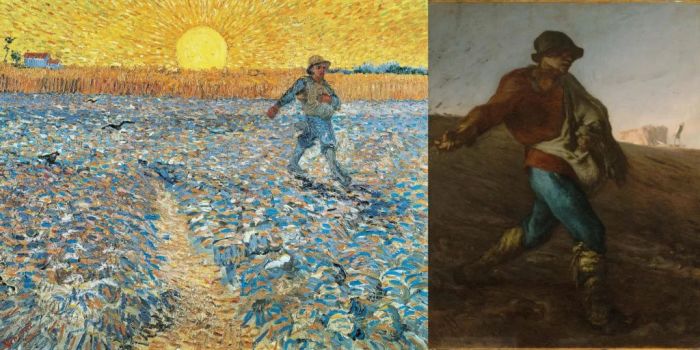

The most striking thread of all for me was this: art is derivative. Sometimes as blatant theft. Sometimes as admiration. Sometimes in defiance. Sometimes ironically. Art seemed to be almost always—at least in some way—a copy of a copy of something. New styles rebel against their predecessors. Click. Artists influence other artists. Click. New creations are fused together from old ones. Click. Art was one big copy machine. And that thing was always running.

Left: Vincent Van Gogh, The Sower (after Millet), 1888, 64,2 x 80,3 cm, oil on canvas, Kröller-Müller Museum.

Right: Francois Millet, The Sower, 1850, 101,6 x 82,6 cm, oil on canvas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Even though the images created by DALL•E are unique, they’re actually the product of millions of other images created by someone else. When users invoke an artist’s style in MidJourney, it’s one that was refined and perfected by a human being. Is this the same kind of master study that has been going on throughout art history, or is this something different?

“A lot of the famous artists who use the platform, they’re all saying the same thing, and it’s really interesting. They say, ‘I feel like Midjourney is an art student, and it has its own style, and when you invoke my name to create an image, it’s like asking an art student to make something inspired by my art. And generally, as an artist, I want people to be inspired by the things that I make.’”

— David Holz, MidJourney creator, in his interview with The Verge

Art history used to be a reference, but text-to-image tools are turning it into an interactive plaything. You don’t have to guess what the artwork of Monet’s and Michelangelo’s imaginary lovechild would look like. You can find out for yourself. If you’re wondering how your sketch might look as graffiti, you can upload it to DALL•E and change your prompt.

The spice of life.

During my time working with creative people—especially visual creators—I’ve learned that we all have crutches. There are these reflexes that automatically activate, especially during periods of stress, or difficult time constraints. We fall back on habits, cliches, familiar speech patterns, proven compositions, favorite fonts, and other tried and true tropes, as heuristic life rafts. We’re striving for novelty and variety, but our default is more of the same. For our new breed of image making tools, however, the opposite is true.

The “everywhere girl” appeared in ads for Dell and Gateway that were running at the same time in 2004, thanks to each company’s embarrassing reliance on stock photography, and our human tendency to repeat ourselves. If you think you’ve seen a person in an ad before, you probably have, because for humans, variety is hard.

Variety is the default mode of AI-powered image generators. Not just more variety—infinite variety. It’s one of the key features of tools like Midjourney and DALL•E, and it’s central to their appeal and utility. Because each generation begins with random noise, and non-deterministic calculations, the results are mathematically distinct. And what could be more interesting than that? So that image you just created with MidJourney will literally never be created again. Even if you use the same prompt, the output will be unique. Which could mean the death of digital déjà vu.

Generation process for “unique new york,” created with MidJourney

A quantum leap in quantity.

When NASA hired George Land to help them identify the brightest minds with the right stuff, he came back with a simple test to measure creativity. The challenge was a single question: how many uses can you come up with for a paperclip? Land and his colleague, Beth Jarman, tested people of varying ages, and the results were staggering: 98% of 4–5-year-olds demonstrated genius-level imaginations, while adult geniuses topped out at 2%. Kids came up with more ideas than grown-ups. The un-learning of creativity is a topic best saved for another time, but Land’s methodology proves something I think we all know, instinctively: creativity may be difficult to measure, but quantity, not quality, of ideas is the best predictor of success. And when it’s a numbers game, computers will always have the upper hand.

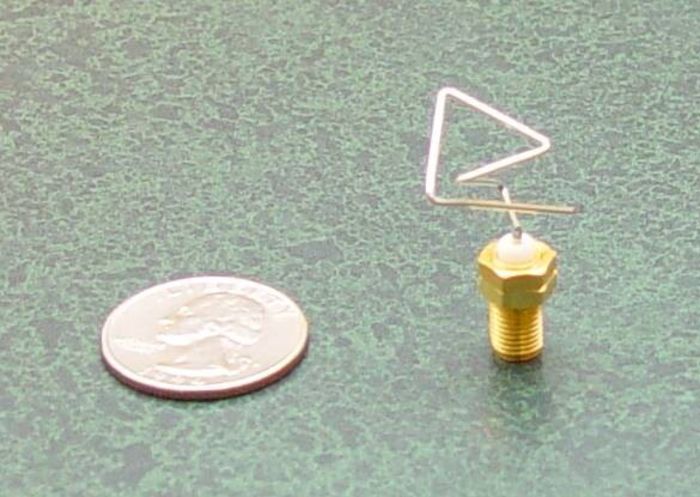

Evolutionary algorithms explored countless design possibilities to outperform the designs of NASA engineers when creating an antenna for their ST5 spacecraft.

The whole reason we even have machine-learning-based AI is because of the incomprehensible number-crunching capacity of contemporary computers. Artificial intelligence has surpassed human intelligence in innumerable ways. Computers are better than us at games. They can perform diagnoses better than human doctors. And despite their paperclip quiz, NASA has shown that computers beat engineers at designing an effective antenna (that, in a strange twist of irony, kind of looks like a paperclip). Why? They try more ideas. And AI supercharges that ability.

As NASA engineer Jason Lohn said, “No human would build an antenna as crazy as this.”

In the same way that kids are less inhibited to explore zany ideas, computers don’t have to pre-filter ideas before testing them. They can just test everything. When it comes to image making, getting to quantity is an endurance battle. It’s a slow process. Things like creative block, fear of failure, and other annoyingly human traits slow us down even more. Our human inputs are tedious and massive, and our output is a single image. But with AI image-generating superpowers, our ideas can materialize and multiply as fast as we can type. Now our inputs are minute, and the outputs are infinite. Quantity of visual approaches is limited only by the ideas we’re willing to explore, not the time it takes to select and bring each one to life.

“macro photograph of a paperclip in the shape of an infinity symbol,” created with DALL•E

A word after a word after a word is power.

For me, finding the right words is like getting the last blops of ketchup out of a glass bottle at a diner: lots of shaking and tapping, sometimes a knife is involved, a bunch of awkward contortions, and then, if I’m lucky, a seemingly random burst of flow makes a big mess. Fortunately, my career has paired me with absolutely brilliant writers, and thank God. As far as I’m concerned, anyone who takes on a blank page or screen armed only with words might as well be charging into a burning house with a firehose. I salute you brave writing souls. I’m much more comfortable creating images. But all this new tech is forcing the issue.

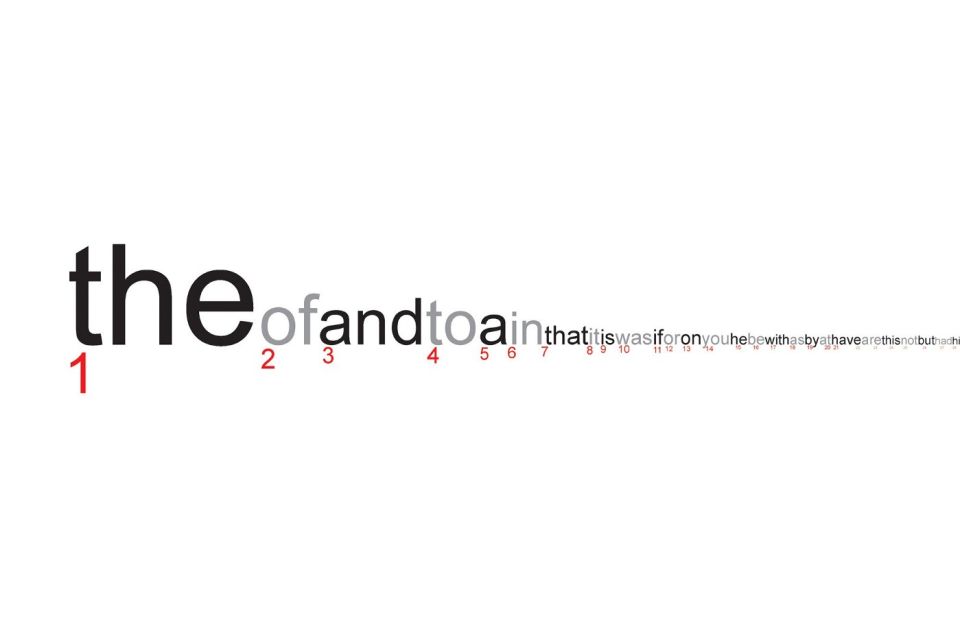

In 2004, Jonathan Harris created an interactive infographic at wordcount.org that arranged the 88,000 most used English words end-to-end, ranked in order of commonality according to the British National Corpus. It was a beautiful illustration of the contrast between the vastness of language and the small fraction of it we actually use. We can account for one-third of all printed material in the English language with only 25 words. 100 words make up about half of all written English. George Kingsley Zipf popularized this phenomenon another way, observing that the most frequent word (“the”) will occur about twice as often as the next most frequent word, and so on. Zipf’s Law has since been applied more broadly to all kinds of physical and social science data.

Traditionally, the advertising world has had two main ingredients: art and copy. Not always, but often, art precedes copy in the creative process. An art director might arrive at a concept visually, and then work with a writer to fill in the words post-factum. Now, however, the image making process might begin with a careful selection of words—not as a headline, or body copy, but as a way to actually generate the image. In this new world where the raw ingredients for images are words, creators need a deep visual and verbal vocabulary.

“verbal, visual,” created with MidJourney

Being misunderstood is painful—it causes stress and lowers life satisfaction—and yet, creative types will subject themselves to it over and over. When a writer and designer are paired to collaborate on ideas, this pain is expected. It’s part of the process. It’s hard to arrive a mutual understanding of something that doesn’t exist yet. Ideas don’t describe themselves. The process to surfacing good ideas starts with a hopeful “what if…” and devolves from there. The designer reflexively starts sketching. The writer starts slinging similes. Each person defaults to their creative love language. Collaborative creation is a thrashing, masochistic, mental mosh pit. Sentences inevitably conclude with a trailing gasp, “…you know?” And for an idea, the answer to this question is a matter of life and death. Most ideas don’t survive the litmus test; often, the answer is no. “No, I don’t get it.” But what if the answer was always yes?

“typewriter, paint,” created with MidJourney

Text-to-image tools are like a visual babel fish for ideas. This new tech language can help us speak the same one. You can kind of beam someone into your imagination instead of relying on words alone and hoping they understand what in tarnation you’re talking about. With MidJourney and DALL•E as universal translators, creative collaborators are free to spend less time trying to understand each other’s ideas, and more time exploring them.

You might argue that our search-engine-default brains have already evolved this way of working into standard practice. After all, isn’t that kind of what we’re doing with Google Images right now? Well, kind of, but the critical difference is that we’ve moved from searching to generating. When the words we choose change the results, those words have new power.

“35mm light leak wide shot photo of an infinitely tall pile of colorful plastic letters reaching the sky,” created with DALL•E

Define zebracowfish.

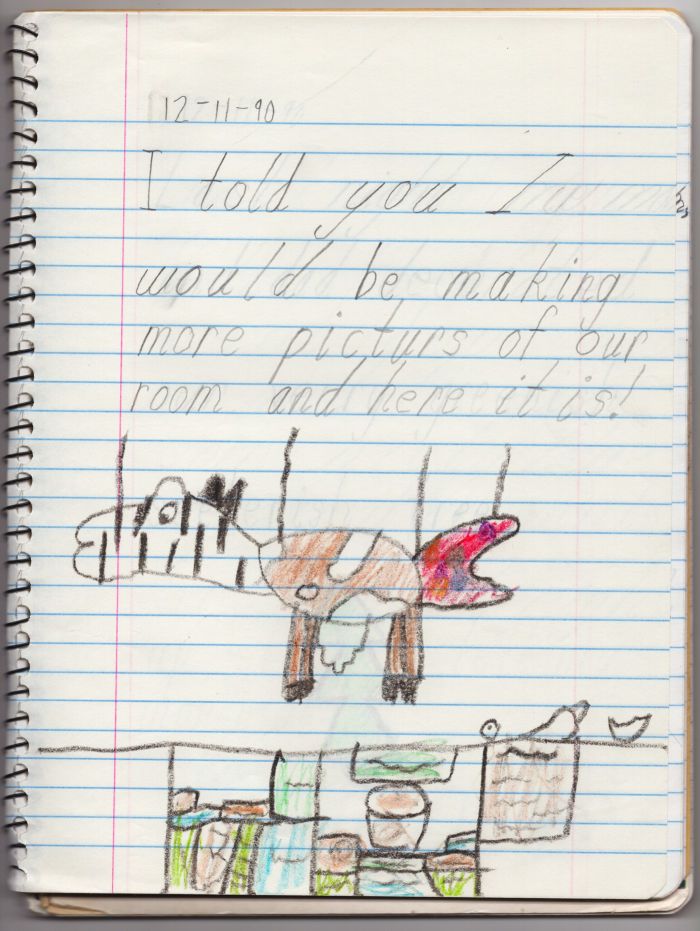

Computers didn’t exist, for me, until the fourth grade. Before then, school was synonymous with manual labor, in the literal sense. For anyone touring McClure Elementary School in 1990, two things echoed through the halls: the tiny squawks of kids parroting rote knowledge, and a flurry of busy fingers scrawling a short story onto a Big Chief tablet, or ripping apart the velcro of a Trapper Keeper to hand-in a worksheet. The hallway was a gallery of doors framing all the action, every one left open for public display—except for one.

My first-grade teacher, Mrs. Johnson, was gentle and radiant. A fellow Roald Dahl fan, she believed in something so sacred that for a portion of each school day she drew the blinds and locked her door to protect it for us. She held a view that was, at the time, an unpopular one, at least with her principal and colleagues.

She believed that art was important. And even though it wasn’t prescribed in the USD 501 curriculum guidelines for 6 and 7-year-olds, she let us enjoy it everyday. She seemed to be convinced I might even be good at it. I like to think this had little to do with my Crayola-wielding skills or overall manual dexterity, but something more she was seeing in me that I couldn’t. When she locked that door, she unlocked a defining aspect of my identity, and a source of joy that persists today. I’m forever grateful.

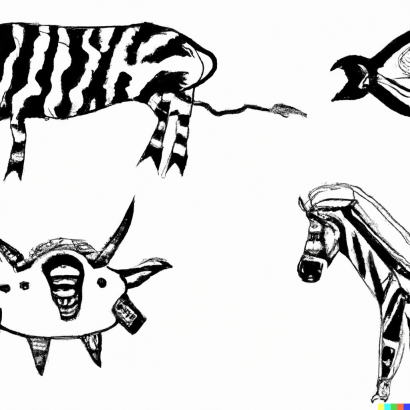

Shrouded in creative sanctuary, about halfway through every year, each of Mrs. Johnson’s first grade classes received the same creative brief. We were prompted to combine three animals into a new species, to be illustrated with an enormous, stuffed, paper sculpture that would hang prominently from the ceiling of our classroom for the remainder of the school year. As Kindergarteners we had seen the work of our predecessors proudly exhibited, so anticipation was running high.

After much deliberation, the class was aligned. The three animals embodying our collective mass of creative genius and securing our legacy were decided: the zebra, cow, and fish. (The choices were obvious when you really stopped to think about it.) Our zebracowfish was magnificent. Such a creature could only be born from the minds of 20 first graders.

A page from my 1st grade journal. The zebracowfish is the only illustration to appear more than once.

As the ultimate technology-versus-humanity death-match, it seemed fitting to give our new breed of AI image-makers the same brief. Would MidJourney and DALL•E make Mrs. Johnson proud? How would synthetic image generation fair in producing its own zebracowfish?

Um. Not so great, it turns out.

A couple years before I entered the first grade, Hans Moravec, the renowned futurist, postulated that the things we find difficult (differential calculus, language translation, cancer diagnosis) would become trivial for machines, and the ones we find easy (identifying a crayon and picking it up to draw something) would continue to be a struggle for technology alone.

“It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers, and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility.”

— Hans Moravec, Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence

Today we call that Moravec’s Paradox, and as it relates to besting a class of first graders in Mrs. Johnson’s creative challenge, it seems he was right. There’s no question that AI is amplifying our abilities, but it doesn’t seem to be replacing our unique offerings as human beings. At least not yet.

I’m not sure the giant paper-filled beast on display through the (now-open) classroom door had anything to do with it, but somehow, Mrs. Johnson reached into the latent space of our first-grade selves and found a bunch of artists. The computer stuff came later, but the creative part was always there. As Picasso pointed out, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain one once we grow up.” I think my zebracowfish co-creators would agree.

It’s up to us.

If we could mine all the data from our lives and pass it through a neural network to form a model of ourselves, what would we find in its latent space? What biases would it reveal? Which ingredients would leave the strongest flavors?

Clearly Mrs. Johnson weighed heavily in my life’s model. James and the Giant Peach, locked door, zebracowfish… Other impressions were less obvious. But, without exception, the most impactful influences were also the most humane.

My art history professor was an absolute technological fossil, but that fact didn’t render her any less effective as a teacher. Quite the opposite. In fact, her insistence on that crusty projector of hers is proof that what she inspired in me, through her words and images, was an act of humanity, not technology.

The “stock issues” of policy debate are still easy to recall, thanks to Kuhns (and an acronym discovered with some lingering middle school humor): significance, harms, inherency, topicality, and solvency. But it wasn’t the data he relayed, or the evidence we churned out of his copy machine, that transferred the knowledge. It was his buoyant wit. His raised eyebrows raised questions inside me.

“If we could mine all the data from our lives and pass it through a neural network to form a model of ourselves, what would we find in its latent space?”

Kuhns was a firehose of information when it came to the art of arguing, but he didn’t talk much about flying. His pilot’s license was a sort of secret superpower. You had to pry it out of him in conversation, between tournament rounds, or after class. But with the right prompts, he became more colorful.

It turns out, when he was up there in his two-seater, the world disappeared below him. It was fast, and thrilling, and beautiful. But then he drove home, went to bed, woke up and got back to work in the morning. Someone had to plug in our copy machine.

Neither that copy machine, nor the computer that replaced it, ever won a single round of debate. They only filled our briefcases and brains with inspiration.

The rest was, and is, up to us.

“looking up at a two-seater airplane disappearing into the sky above a tiny yellow ranch-style house,” created with DALL•E

Originally published by Andy Wise on Medium.